The Making of a Decision - Part 2

This series covers the topics described in this talk. This is part 2 of the series about decision making in software systems.

- The Making of a Decision - Part 1

- The Making of a Decision - Part 2 - This article

- The Making of a Decision - Part 3: Tools for Decision Making (coming soon)

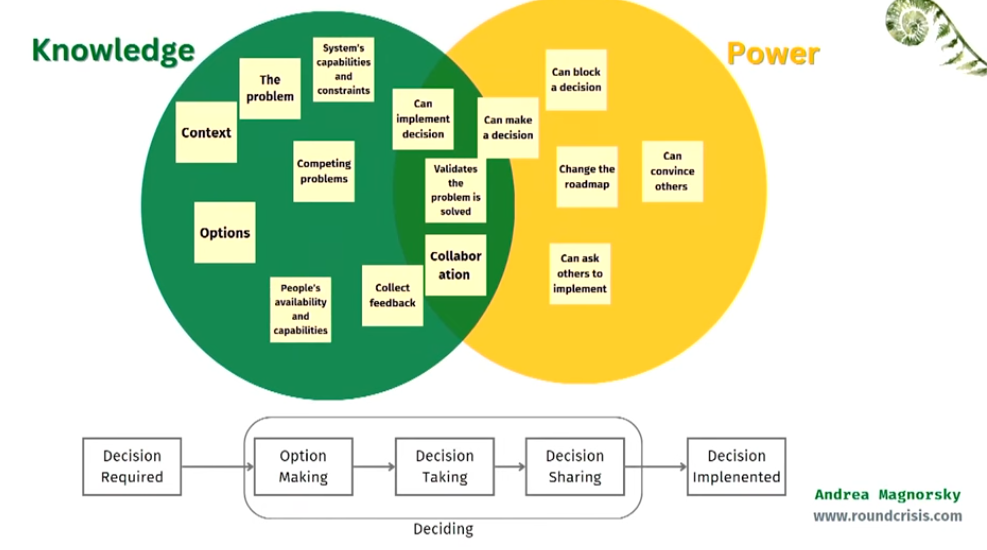

Part 1 of this series explored how power shapes organisational and architectural decision making by reviewing definitions, laws of power and more. This article focuses on knowledge.

We need to know and understand the context to build good systems. What does it mean to know something? What does it mean to know it in the context of an architectural and system design decision?

“Knowledge sharing is (an essential task of) systems building”

Knowledge sharing is systems building (March 2023)

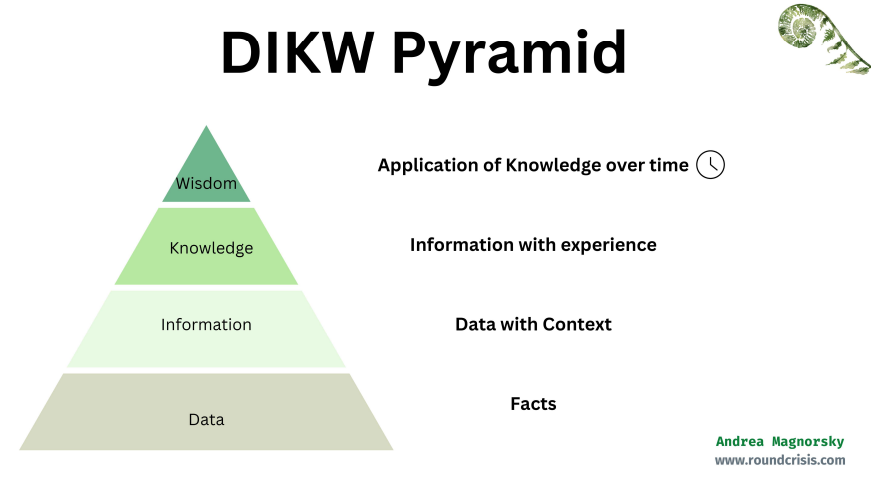

Understanding Knowledge: The DIKW Model

I spoke with Dawn Ahukanna when preparing this talk. She introduced me to the DIKW pyramid as a good starting model for reasoning about knowledge.

The DIKW model makes it clear that context is the bridge between data and insight. Data turns into information only when it’s interpreted within a relevant context, and it becomes knowledge when that information is applied repeatedly to gain experience. At the top of the pyramid sits wisdom, the least developed layer, demanding moral deliberation and the ability to apply knowledge across situations.

Applying DIKW: A Practical Example

This model might be a good starting point for everyday decision making. For example, imagine you learn that a library your organisation heavily depends on has changed its licence and will soon require a large fee for commercial usage. How can the DIKW model help you guide some of your next steps?

-

Data. The facts. The licence change to be introduced in the next version includes a large fee for usage in commercial settings.

-

Information. Adding context. The raw facts are interpreted and linked to the organisation’s own environment. For example, in the near future, the organisation will be liable to pay a significant amount to keep using this library. At this point you should know exactly the cost for a given period. Perhaps you would also know the cost of migrating to another library, although the figure might not be precise. Members of the organisation understand what changed, where it matters, when it will start affecting the system and why.

- Knowledge. Understanding and gaining deeper insights. With the contextualised information, some resulting activities might be:

- Conducting a survey of alternative libraries to find viable drop‑in replacements

- Estimating the cost of replacing the library across the organisation

- Considering security risks associated with onboarding a new library

- Looking back at a similar licence changes and its effects within the organisation

- Discussing with product owners, operations, finance, etc to understand acceptable service interruption or other disruptions

- Paying the licence fee

These activities would help build a coherent body of knowledge: the organisation now knows why the change is problematic, how severe the impact could be, and what realistic options exist.

- Wisdom. Judgement informed by values and strategy over time. Based on knowledge, the organisation is able to exercise broader judgement leveraging their people. At this point you might consider:

- Creating policies. To avoid future vendor lock‑in, and another policy to monitor critical dependencies with a regular cadence

- If migration to a new library is necessary, provide default paths while recognising that this might not suit all teams and prepare for the extra cost in time and money

- Notifying customers. If it’s deemed necessary, with a brief notice explaining the migration and reaffirming the commitment to security and reliability

- Updating the dependency‑management operating procedure. Reviewing whether a mandatory licence‑compatibility check should be required whenever a major version bump is announced

Wisdom here combines technical facts with ethical, financial and strategic considerations, producing a holistic stance rather than a reactionary fix.

For an extensive analysis of the DIKW pyramid please see: The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy- Jennifer Rowley Bangor Business School, University of Wales, Bangor, UK.

The DIKW model gives us a structure for understanding knowledge. The people involved in deriving it are Knowledge Workers.

Knowledge Workers

People who create software systems are knowledge workers. It’s very likely the person reading this is a knowledge worker.

Knowledge workers are workers whose main capital is knowledge. These are workers whose job is to “think for a living”.

source: Thinking For A Living: How to Get Better Performance and Results From Knowledge Workers. Davenport, Thomas H. (2005).

Our output is primarily thinking. The artifacts we create are in support of that thinking. Our capital, our stock, is the things we know. In the context of an organisation, knowledge work is applying knowledge in such a way that solves perceived or real customer problems.

Given that our main capital is knowledge, how can we share it effectively? How can we reason about using it in the most useful and innovative ways?

A Systems Lens

As Donella Meadows wrote in her book Thinking in Systems:

“A system stock is just what it sounds like: a store, a quantity of material or information that has built up over time. It may be a population, an inventory, the wood in a tree, the water in a well, the money in a bank… Stocks change over time through the actions of flows, usually actual physical flows into or out of a stock–filling, draining, births, deaths, production, consumption, growth, decay, spending, saving. Stocks, then, are accumulations, or integrals, of flows.”

It is surprising that as we are building software systems, we rarely apply systemic concepts to our problems, including knowledge management. Diana Montalion addresses this in her book Learning Systems Thinking. In chapter 6, she invites us to consider:

Knowledge Stock: This refers to the store of knowledge a knowledge worker has developed or can access.

Knowledge Flow: The ability to transfer knowledge between people and people and systems in ways that change and shift the system in an effective way.

As an industry we tend to highly value the stock of knowledge, and not so much flow. Without knowledge flow it would be impossible to build systems. Reading further on this I discovered flow is essential to innovation.

Innovation

Most organisations actively pursue innovation in what makes them unique, as a way to ensure their growth and longevity. Given how critical innovation is to organisational survival, researchers have extensively studied what makes organisations innovative. Multiple papers examine the relationship between knowledge sharing and innovation. The results are consistent. As one study clearly states:

“Knowledge transfer among employees is thought to be crucial determinant of an organisation’s capacity to utilise new knowledge and innovate.”

Source: Relationships between knowledge inertia, organizational learning and organization innovation by Shu-hsien Liao, Wu-Chen Fei, Chih-Tang Liu

As an industry, we have known for many decades that the need for knowledge transfer is essential to build and maintain complex software systems.

Historic Lens: Continuity of the “Theory”

Peter Naur’s seminal paper from 1985, Programming as Theory Building, talks about the importance of people carrying the theory of the program or system:

” Thus, again, the program text and its documentation has proven insufficient as a carrier of some of the most important design ideas”

I want to stress that the paper focuses on core design ideas of a program. The paper continues:

“The conclusion seems inescapable that at least with certain kinds of large programs, the continued adaptation, modification and correction of errors in them, is essentially dependent on a certain kind of knowledge possessed by a group of programmers who are closely and continuously connected with them.”

We’ve known for over forty years that stable teams are essential to maintaining the program theory, especially important as systems grow more complex. Yet as an industry, we keep repeating the same Sisyphean cycle, and act surprised each time the boulder rolls back down. Ironically, we do this in the name of cost effectiveness.

The Hidden Barrier: Who Gets to Know?

Throughout this article, we’ve discussed how knowledge transforms into wisdom and flows through organisations. Do organisations accept knowledge from everyone within? Whose knowledge is deemed legitimate in the first place?

This is an ethical amd practical concern too, directly impacting decision quality. As Iris Meredith explores in “Who has permission to know things?”, corporate epistemology determines which voices are heard and which expertise is valued. When organisations systematically invalidate knowledge they don’t just create workplace frustration, they cut themselves off from crucial insights.

“Knowledge is largely defined and controlled by those in power”

This structural barrier is why many organisations experience sudden “explosions”, accumulated resentment and overlooked expertise finally surfacing when problems become unavoidable. Building better decision making systems requires us to consciously examine: Whose knowledge are we excluding? What is it costing us?

Conclusion

The DIKW model provides a useful framework for moving from data to wisdom. Understanding knowledge workers and the importance of knowledge flow matters for innovation and outcomes, yet many organisations have yet to fully grasp this. At the intersection of knowledge and power sits a crucial question - whose knowledge is accepted? When changing an entire organisational culture proves difficult, recognising the barriers to knowledge sharing offers a practical starting point. Stable teams are essential for preserving the “information theory”, or domain knowledge, of a system. When seeking better ways to manage information, preventing its loss in the first place is remarkably efficient.

As a side note, I’ve long held the intuition that a key indicator of an organisation’s health is the time its people dedicate to learning, particularly when they learn together about their systems, and keep thinking of ways to validate or invalidate this intuition. If you have thoughts or comments about this or anything to do with this article please let me know.

I hope you enjoyed the second part of “The making of a decision”. The next post will be about tools that we can use to improve our decision making in terms of knowledge and power.

Resources and Extra Reading Materials

Core Concepts

-

The wisdom hierarchy: representations of the DIKW hierarchy- Jennifer Rowley Bangor Business School, University of Wales, Bangor, UK This paper revisits the Data–information–knowledge–wisdom (DIKW) hierarchy by looking at how different textbooks explain the hierarchy in a number of widely read textbooks, and analysing their statements about the nature of data, information, knowledge, and wisdom.

-

Programming as Theory Building - Peter Naur (1985). Seminal paper on the importance of maintaining program theory through stable teams.

-

Learning Systems Thinking - Diana Montalion. Explores systemic approaches to knowledge in organizations.

Knowledge and Power

- Who has permission to know things? - Iris Meredith. Explores how corporate epistemology and power structures determine whose knowledge is valued.

Decision Making

- Slow down to speed up your decision-making - Gien Verschatse

Related Research

-

Relationships between knowledge inertia, organizational learning and organization innovation - Shu-hsien Liaoa, Wu-Chen Fei, Chih-Tang Liu. On knowledge transfer as a determinant of innovation capacity.

-

Charisma in Everyday Life: Conceptualization and Validation of the General Charisma Inventory - Konstantin O. Tskhay et al., University of Toronto.